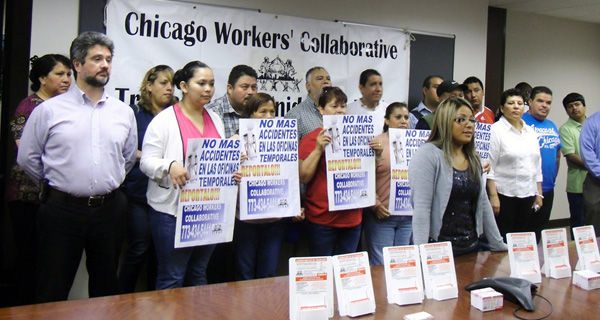

Representatives from the advocacy group Chicago Workers' Collaborative are taking OSHA to task for historically failing to protect temporary low-wage workers. (Chicago Workers' Collaborative)

Rosa Ramirez, a 49-year-old Mexican immigrant and mother in Illinois, knew something was odd about the plastics factory where her temporary-labor agency had sent her. "From the minute one walks into that factory, one is hit by this incredible odor of [chemical] thinner ... It just goes right through you,” she recalled through an interpreter in an interview with Working In These Times.

But soon, the noxious smell was the least of her concerns. While making plastic molds on her first—and last—day in April, Ramirez suffered a searingly painful burn on her hand. When she tried to report the injury to her temp-work agency, Staffing Network, she says dispatchers laughed at her and called the wound minor, pressuring her to drop the issue.

Looking back now, she remembers seeing several other people at the plastics factory with burns on their arms and hands. But as Ramirez points out, many temporary workers don't report injuries to avoid potential employer retaliation. “[We're] very afraid of saying anything for fear of losing our jobs,” she says, who notes that she hasn't been called back to work by Staffing Network since she, as she puts it, "stood up for [her] rights."

Temporary workers, or "temps," often go into work every day without even knowing what their job will entail, let alone what safety precautions they should take. These “contingent laborers" form a growing share of the workforce that is increasingly anonymous, dispersed, disorganized and, sometimes, in dire danger.

Temps occupy nearly every sector today, including day-labor builders, office staffers and food-processing workers. They may be stepping in as you vacation this holiday season, running Big Box retail warehouses on Black Friday or fulfilling your gift mail-order. The one thing all these positions all have in common, though, is their high "cost-efficiency." This labor pool is usually indirectly hired by companies through subcontractors, allowing the company to generally avoid dealing with contracts, pensions, unions or organizing by workers—and to have an additional buffer against liability when workers fall at a construction site or faint from chemical fumes. And the temps who fill these roles--who comprise an estimated 2.8 percent or more of the workforce—are disproportionately female and of color, further reinforcing the systemic gender and racial inequalities present in the American job market.

According to the worker advocacy group Chicago Workers' Collaborative (CWC), of which Ramirez is now a member, the group’s temp members earn just $11,000 per year on average and “labor for minimum wages during short periods of time without any benefits such as sick days, holidays, vacations, or health insurance.” Whether they’re just trying to make ends meet this month or have become long-term "permatemps," they form part of a seldom-regarded workforce that provides contracted manpower and logistics services for some of the largest and most prominent commercial brands, such as Wal-Mart and Nike.

Labor advocates like the CWC worry about keeping low-wage temp workers safe, especially those who do manual labor like front-line assembly work or furniture movement. Given that the Occupational Safety Health Administration has historically left the temp sector relatively unprotected, when workers line up at staffing agency offices each morning, they often have little hope of being adequately prepared for the hazards they may face.

With this in mind, the National Council on Occupational Safety and Health, an independent advocacy organization, together with various labor and safety groups, recently issued suggested guidelines to OSHA, emphasizing that temporary workers are frequently thrust into jobs that demand comprehensive safety training but given little support. The group called on the agency to issue rules that clearly delineate the responsibilities of "host employers"—the corporations using the workers supplied by labor brokers—and temporary staffing agencies that do the hiring and to establish clear standards for workplace-safety training. Another recommendation was to establish a more comprehensive workplace inspection process and do outreach to inform workers about their right to report safety problems. OSHA, for its part, has announced plans to ramp up its regulatory action in the temp industry.

In the meantime, much of the burden of keeping workers informed about safety issues and their workplace rights falls on workers like Ramirez, who, in her campaigning with the CWC, has developed a special safety committee with fellow temp workers. But the low-wage industries she’s confronting are employing workers at a far greater scale than she can educate on an individual basis. Right now, she’s worried about dangerous conditions at another Staffing Network workplace, an Illinois food-processing plant called Great Kitchens where CWC advocates say many workers have gotten hurt.

When the CWC requested injury data for those workers from the administration of Staffing Network, the agency wrote back in September, "we are not required, nor do we maintain an OSHA Form 300 (log) for our temporary employees assigned to work at our client companies." Staffing Network has separately defended its labor practices in response to a ProPublica investigation on the temp industry last summer.

But according to Ramirez, the temp agency asks workers to report any injuries directly to Staffing Network rather than to the plant. In turn, because Staffing Network claims it doesn't have to formally log these incidents, the CWC fears many injuries may ultimately go unrecorded. When the CWC obtained information about the injuries that workers did report to Great Kitchens, it found a list of dozens of workplace incidents there during the past two years that included wrist sprains, back strains and head laceration.

Even while advocates try to increase employer accountability for worker safety, though, the temp sector continues to expand. Symptomatic of a long-term trend of eroding job security, with companies reluctant to hire full-time positions, temping has absorbed many people who lost regular jobs as well as younger workers who are finding their post-school job options dismally narrow. “Staffing firms accounted for 20,000 of the 148,000 jobs the nation added” in September, the Wall Street Journal reports. It seems there’s an army of temps lined up to help heal the battered economy, even at the risk of getting hurt themselves in the process.